Pro athletic initiatives spur change

Concussions as hot-button issue in media trigger response at school level

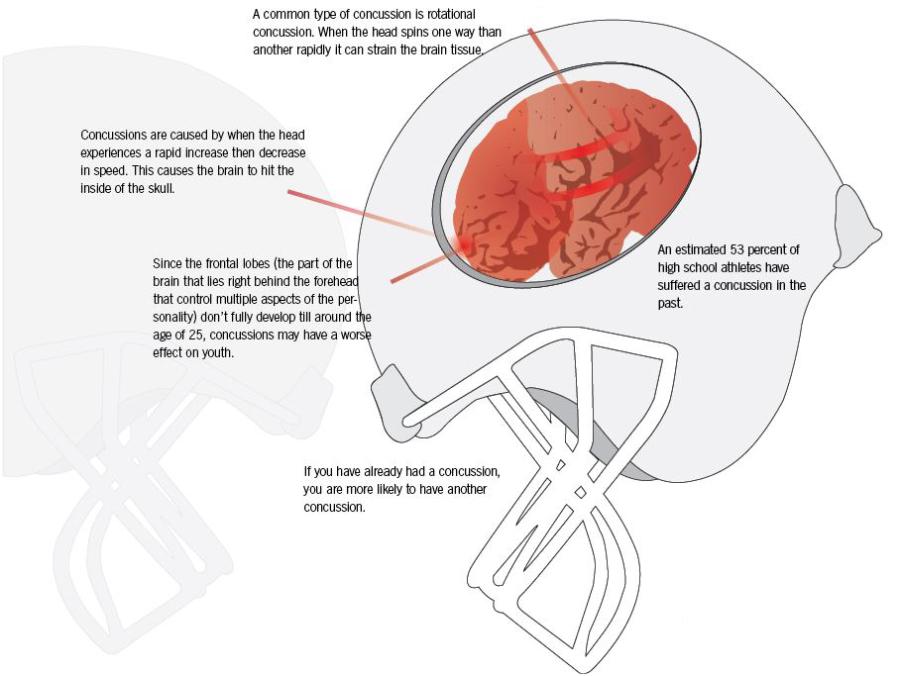

Graphic By Nick Steichen

November 14, 2014

Among the countless lawsuits that pop up in professional athletics, it is not often that thousands of former players sue an association for the same issue.

Yet, the National Football League in July settled a multi-million dollar agreement that holds the NFL accountable for the cost of medical treatment for former and current players. The claim was filed by more than 4,500 former players who now suffer from neurological issues because of the lack of proper concussion recovery.

In light of the alarming frequency of ALS, dementia and suicide among former professional football players, concussions are being taken more seriously, and the NFL has addressed the problem publicly and taken initiatives to raise awareness in young players.

“A lot of that came to light and then prompted more research,” athletic trainer Jeremy Goats said. “Because when you get these multi-million dollar lawsuits and high-profile players suing…it definitely puts a spotlight on it.”

For parents and athletes, the news out of the NFL has been troubling. According to an article on ESPN.com, the concussion issue was first recognized by the NFL in 2005 when researchers found that a large number of former players had neurodegenerative diseases. In 2009, a Congress committee questioned NFL commissioners about the league concealing the link between concussions and later neurological problems.

When the research came out, many doctors and parents became concerned about youth who begin contact sports at a young age. In fact, just following the release of the studies, Pop Warner football data reflected that participation in the sport for youths dropped substantially. While there isn’t a direct correlation between the studies and participation, many believe fear of injury has stifled participation.

“It definitely has affected our number a little bit, it has to,” Goats said. “Because there are some parents that just won’t let their kids do contact sports.”

According to Goats, there have been 13 concussions across all fall sports teams, a fairly low number compared to years previous.

While football shows the highest rate of concussion the school deals with, they are also common in other contact sports such as soccer and wrestling.

Goats says that player-for-player soccer may even present a higher frequency of concussions.

Although there may be some prejudice against contact sports, lawsuits have prompted not only studies, but safety initiatives have trickled down to youth education and prevention, especially at the high school level.

USA Football, for example, advocates for a “heads up” tackle technique to prevent head-to-head collisions and lessen the chance of brain damage.

The football coaches have implemented the technique and take time before full-pad practices and scrimmages to to review it.

“We put them in the best equipment money can buy,” Wedd said. “Our helmets… have the highest test for safety on the market, so I feel like our kids are wearing the best equipment…. and then we also teach them how to tackle correctly, how to block correctly, because that is important too, and we film everything so that they have had the correct instruction.”

Although the athletic department takes precautions against head injuries, concussions are a common occurrence, particularly in contact sports such as football and soccer, and are often times unavoidable.

“You can have the best protective padding, you can have the best ‘fill in the blank’ at some point, there is still the likelihood that someone is going to get a concussion,” Goats said.

In light of this, the athletics program has recently focused on concussion testing and management to ensure brain injuries that do happen are lower in severity and don’t become a recurring issue.

In the past few years, the school has offered the ImPACT neuro-baseline test, which is optional to all athletes and can detect changes in cognitive function.

In principle, athletes are to take the test their freshman and junior years before season, and the results provide a benchmark for their general mental performance. If the student is injured, the test provides a baseline for comparison.

Although the test is not mandatory, Wedd said between 80 and 90 percent of his players take it. It is free.

Goats envisions a more widespread solution.

“I definitely see them implementing a mandatory test for the athletes,” he said.

The athletic department has also changed the way it classifies and responds to brain injuries.

In the seven years Goats has been at LHS, the state has administered new standards for concussion recognition and management, primarily ensuring that injuries are handled on a case-by-case basis.

Opposed to being classified into a specific category, athletes are not allowed to play until they fully recover.

“The primary thing… is that the kid has be be asymptomatic, which means they need to be without symptoms for 24 hours until the can start a return-to-play progression,” Goats said.

The athletic program has implemented a five-step standard all athletes returning from concussions go through before being reintroduced into play. The progression ensures that symptoms are entirely gone before athletes are back to full-contact play and can be slowed down if more recovery time is needed.

However, even with team initiatives to catch potential injuries quickly, players may know best when they have been injured. But, they sometimes try to conceal their symptoms.

“I think they do sometimes because they really stress how even minor headaches can be a sign for a concussion,” Goats said. “Some players just want to play. They do just like they would an ankle injury, knee injury or a knee injury… I know that some would try to hide it. But in the end it’s going to come out eventually, and at that point, they set themselves back, and it takes them more time to get back.”

Wedd said his players understand the severity of concussions, and teammates watch out for their fellow players to ensure no one is overextending themselves.

“I think nowadays kids know the severity of head trauma,” he said. “We will see a big hit every once in awhile and some of the other kids will point him off the field, because he is either talking funny in the huddle, and they know something is wrong. They are pretty good that they are being safe out there also.”

Some students have not only been educated on the subject but have experienced the severity of head injuries.

Senior Sammy Tuckwin got a serious concussion his freshman year that affected his physical health and academic performance.

“I can’t strain my brain, and I can’t get stressed.” Tuckwin said. “I had to retake geometry freshman year.”

While having to retake a class is more severe than most athlete’s consequences, the Sunflower League has recently seen some tragedies that further the awareness of sport-related brain injuries.

Most recently, Olathe East football player James McGinnis collapsed during a game last month and subsequently went into emergency brain surgery due to blood clots in the brain possibly caused by high-impact collisions prior to the game. He is currently in rehabilitation, and is projected to be fine.

“Everything has made us be more conscious of kids,” Wedd said. “We had a young athlete die last year…from an aneurysm at Shawnee Mission West… The Olathe East kid is having a good path to recovery, and we are excited… he is being rehabbed right now…”

In the US, about 225,000 kids played football starting from the time they are young children. In the realm of youth athletic initiatives, there is strong emphasis on reducing heavy contact from a young age.

Goats points out that even in youth leagues there is heavy contact in tackles, and in turn risk on head injury.

“I do agree with the studies that say that when kids have a lot of contact at a young age it doesn’t pay off,” Goats said. “It doesn’t make them any better at the sport by starting at such a young age than if they start it at the junior high and high school levels.”

Wedd has not noticed a fluctuation of numbers of players trying out in the summer since the studies have come out, but he defends participation of the sport for a variety of reasons.

“As a coach you got to constantly reaffirm to parents that it is a safe sport,” Wedd said. “You always what is best for your child, and you always want them to be safe. And I do know this: from 3 o’clock to 6 o’clock the safest place in the world is on an athletic field compared to some of the things kids do between 3 o’clock and 6 o’clock… it is well-worth having adult supervision from that point and the discipline they get in athletics, or in any extracurricular activity… parents need to see the big picture.”