“Get out of here, sand n*****.”

That’s what an elderly man yelled at me while I was hunched over in excruciating pain, walking into the Lawrence Memorial Hospital emergency room.

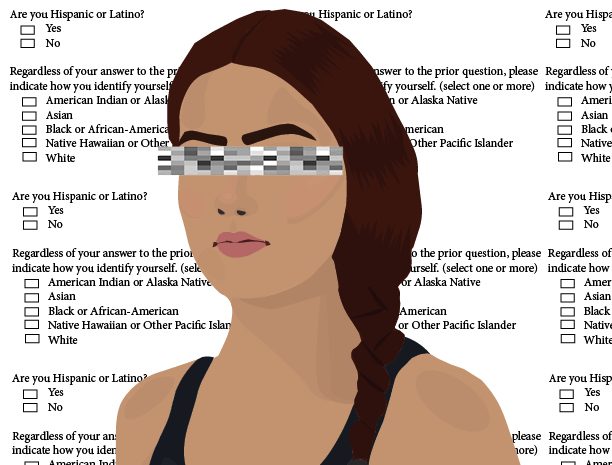

I walked past him into the lobby and was handed a form that asked me to identify as one of these: White, Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. None of which I am.

Flash forward three years. I was walking down the school hallway when a freshman called me a “stupid Mexican.”

I know I’m not stupid. And I know I’m not Mexican. He was wrong about both of those, but at least he knew I wasn’t white.

As a Middle Eastern woman and a person of Iranian descent, my experiences align with people of color. I have grown up facing racial discrimination, being called a terrorist, told to “go back to my country,” and patted down by TSA officers while my white friends could go through the security detector.

.

I am a person of color. I know I am. But the census doesn’t count me as one.

When I fill out a form that asks for my race, I am forced to put down “other.” It pains me to see that although I am counted, I am forgotten. I am just some “other” race. All 3.5 million of us of Middle Eastern or North African descent are just some “other” race.

Without the option to check off MENA [Middle Eastern or North African], our voices are lost in the sea of white people who make up the majority of the United States population.

It seemed like things would change when the Obama administration aimed to change the way we ask questions about race and ethnicity by adding MENA as an option to the 2020 US Census.

But when time came to prepare for the 2020 US census during former President Trump’s administration, the proposal sat on the desks of the White House Office of Management and Budget. This ultimately led to a lack of decision making, muffling the efforts that were taken to bring visibility to people of Middle Eastern and North African descent.

Not only did they disregard the proposal, but they went as far as to add in fine print below the white option “German, Irish, Lebanese, Egyptian, etc.”

We are not white. We are not “etc.”

This is a low blow to people facing invisibility.

This issue doesn’t only affect the identity of Middle Eastern or North African people, but it also determines the way people allocate resources, research health trends in communities, and other important issues that demand accurate statistical information.

I don’t doubt there are many Middle Eastern or North African people who prefer to pass as white. During a time where being white-passing means you get let off the hook more easily by law enforcement, don’t get looks when you speak a foreign language in public, and get to walk through an airport without the fear of someone making a 9-11 comment toward you, it’s understandable.

It makes sense why someone would rather avoid all of those struggles and live their life through a lens of privilege. But that doesn’t mean that preferring to be discounted instead of validated is optimal. It’s a survival tactic.

A month ago, my school counselor introduced me to The Gates Scholarship Program, a “last-dollar scholarship for outstanding, minority, high school seniors from low-income households.”

The scholarship is nationally recognized as this financial resource for minority students. All over its website are photos of students of color that won the scholarship.

It wasn’t until I got to the second page of the application that it asked for my race. I took a long, hard look at it and — once again — didn’t see MENA there. After lengthy conversations with my counselors, I decided to put down Asian. After all, Iran is in Asia.

I thought, “There’s no way this million dollar organization that aims to provide financial aid to students of color, has a whole convention building dedicated to it, hosts a huge award ceremony every year for the winners, and accepts donations for its “cause” doesn’t see me, right? There’s no way.”

It took me to another page that listed numerous countries — ones they counted — in Asia. I scrolled through the list over and over again and finally accepted the fact that the whole Middle East and West Asia wasn’t on the list.

I didn’t know that they had a deficient definition of “person of color.”

My counselor and teacher emailed them. The responses avoided the issue and pointed them to some back page of their website that didn’t address our concerns.

I have experienced this issue my whole life. I have refused to fill out documents because they required me to pick an option that doesn’t fit me. I have left doctors offices because their forms asked to use me as an inaccurate label. When people aren’t seen, communities can’t understand their needs and reflect what resources they require.

Notice our identities the same way you notice our differences. See what we have been through. Account for our unique history. Understand we deserve to be seen.