Schools not notified of students with sex offenses

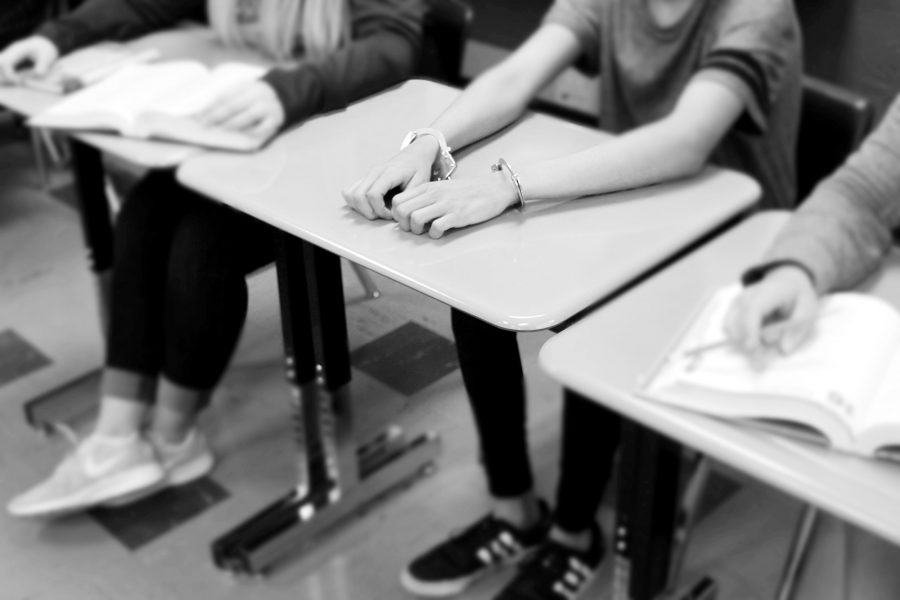

With no notification requirements, schools are unable to make informed decisions if students with criminal offenses need alternative education options.

April 22, 2016

By the time former Lawrence High senior James Gleghorn was arrested late at night in the back of a car with his underage girlfriend, he had been on the sex offender registry for more than four years.

Gleghorn was arrested on Feb. 14 by the Eudora Police Department and later charged with aggravated indecent liberties with a child. In those early morning hours before heading to jail, Gleghorn told police that fellow students found out about his previous 2011 offense: lewd and lascivious behavior and aggravated indecent liberties with a child younger than 14. Gleghorn said he had lost friends because of it, according to the arrest affidavit.

Yet, LHS officials said they weren’t informed of his record by law enforcement or courts, even after the most recent arrest — one of two examples of LHS students who have been convicted of sex crimes.**

Notification of the school by law enforcement isn’t required, as it is in some states. This means that students with criminal convictions may participate in school and extracurricular activities, including overnight trips, without school personnel knowing.

The LHS cases raise questions about the relationship between law enforcement and schools when students commit crimes. Among them, should schools know when they have students who have committed sexual offenses? If so, who should be responsible for notifying the schools? The cases also raise questions about what schools can or should do if they know they have students with sex offense convictions. What consequences might those students face in school? What rights should perpetrators maintain and how should schools look out for victims of sexual assault?

Perhaps the most pressing question, though, is how schools should balance the safety of students with the obligation to educate all students — including students who have committed sex offenses.

Carolyn Wims-Campbell, who represents part of Lawrence on the Kansas State Board of Education, said she was surprised to learn that sex offenders could be in schools without educators knowing.

“We need to be protecting our children,” she said. “When our children come to school, they need to be safe. We say all the time that school is a safe environment, but when you have something like this — this truly bothers me.”

In a school setting, adult sex offenders are treated differently from students who might have the same offenses. For example, teachers must undergo background checks.

In addition, school employees are expected to look out for the safety of their students on and off school grounds. School employees are required to report concerns about students’ safety outside of school to the Kansas Department for Children and Families. However, there is no requirement that law enforcement notify schools when their students are suspected of — or even convicted of — crimes like rape. Even if schools knew, there isn’t any requirement for schools to share that information with the student’s next school if the student transfers.

Although one of the administrators said they found out about Gleghorn’s record informally after he began attending school at LHS, they said the administration was not informed when he enrolled. When they did find out, they said it was through “informal” means. At least one administrator didn’t find out about his record until after the most recent arrest.**

“The police are not required to notify school districts when a student is suspected of a sex crime or any other type of crime,” said Lori Church, an attorney for the Kansas Association of School Boards, which works closely with school boards throughout the state. “They might do so as a courtesy, but there is no requirement for such reporting.”

And in the two cases of LHS students with sex crime convictions this school year, that courtesy was not extended.

IN THE DARK

In addition to Gleghorn, another student transferred to LHS this school year after being charged with two different counts of rape and sodomy in another Kansas town. In November, he pleaded no contest to reduced charges — two counts of aggravated sexual battery.

In this story, The Budget names Gleghorn because his most recent offense was committed after he turned 18. The other LHS student is not named, nor is the Kansas town he transferred from disclosed, because The Budget does not name juvenile offenders. Attorneys for both students declined to comment on their cases.

Although both Gleghorn and the other student were charged with their crimes before starting classes at LHS, the school was not notified by law enforcement or any other entity.

Trent McKinley, the public information officer for the Lawrence Police Department, said there is no requirement for the department to notify schools that have students with criminal records. The police, he said in an email, only deal with the initial investigation of the crime, not the trial or sentencing. Those matters are the job of the Douglas County District Attorney’s office, he said.

However, the district attorney’s office said notifying schools was not its responsibility, either. Cheryl Wright Kunard, assistant to the district attorney, referred The Budget to the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office, whose public information officer redirected the question back to the police department.

Vanessa Hays, the youth advocate with The Sexual Trauma and Abuse Center in Lawrence, said the lack of communication points to a wider problem with how schools address sexual assaults. While schools often have plans to deal with students who are physically violent, she said they also need plans for how to handle students with a history of sexual violence.

“It puts other people at risk [when schools aren’t notified],” Hays said.

It’s unclear just how many students with sexual offenses are in public schools. However, it is likely more common than schools know. In 2015 alone, Douglas County brought sex crime charges against 11 juveniles, according to Wright Kunard. Since 2010, 25 juveniles have been charged with sexual offenses.

Neither the Kansas Legislature nor the Kansas State Department of Education have addressed the issue, said Mark Tallman, a lobbyist for the Kansas Association of School Boards.

Wims-Campbell, the state school board member, was surprised to hear about the issue at LHS and said the issue of student sex offenders should be addressed through a state school board regulation. Already, she said officials have worked to better protect students from adults who might prey on them but the issue of students with sex offenses hadn’t been raised until now.

“I thought now that we would be doing so much better — we are with adults, with the educators — but I think we need to be doing the same thing with our children,” she said.

AT SCHOOL

Gleghorn can no longer attend LHS because one of his bail conditions mandates that he cannot have contact with people younger than 18.

The other student, however, still attends LHS. The student transferred from another county in Kansas and began at LHS this fall. His offenses were against classmates — one 16 and the other 17 — whom he met through extracurriculars at his previous school last year, according to a local newspaper in another Kansas town.

At a Feb. 22 sentencing hearing in the county where the offenses occurred, one of the victims told the court that she hoped he would be restricted from participating in school activities. She also asked that he not be put on the sex offender registry and instead be put through treatment.

“After a fair amount of research and contemplation, I believe [he] should be banned from school club [sic] and be required to undergo both inpatient and outpatient treatment,” the victim said, according to that local newspaper. “He’s a threat to students, and clubs would give him access to future victims.”

Yet, without LHS knowing about the student’s criminal charges, he was involved in activities earlier this year. His case has since been transferred to Douglas County District Court, where sentencing is scheduled for April 29.

Although perpetrators of crimes are entitled to an education, schools are legally able to restrict students, including those with sex offenses, from sports, clubs and other opportunities to interact with students outside the classroom.

“Individual school districts could probably restrict students with offenses from participating in school activities because students do not have a constitutional right to participate in extracurricular activities,” Church said.

Although some students may be listed on the Kansas sex offender registry, schools don’t regularly check that online database. A school administrator, who didn’t want to be named, said it was because there is no effective way to search the list for students. To search the registry effectively, the administrator said, would require devoting a significant amount of time and manpower.

USD 497 school board president Vanessa Sanburn said in instances when schools learn information about a student’s criminal record, that information is shared with teachers when that student’s presence could affect the safety of their peers. However, since juveniles are allowed special privacy rights when they commit crimes, those rights must be taken into account, as well.

“Privacy and confidentiality rights have to be balanced with safety,” Sanburn said in an email. “So often, staff are made aware of student’s past criminal activities, in order to monitor for safety on a ‘need to know’ basis.”

While under juvenile corrections supervision, some students attend school at the Youth Services Detention Center, Sanburn said.

“In certain circumstances, if a student commits a felony-level crime, we are able to expel a student if they are believed to pose a safety risk,” Sanburn said.

But with no notification requirement, the school district doesn’t always know when students have committed felony-level crimes.

POSSIBLE CHANGES

In terms of the law, Anthony Hensley, the Kansas Senate minority leader, said something needs to change.

“I think that those kinds of things should be reported to the school,” said Hensley, a Democrat and longtime educator in Topeka. “The experience that I had while teaching special education at Capital City [School] was that kind of information was well-known.”

Wims-Campbell said she and other state school board members could — and potentially would — create a statewide regulation that would establish reporting requirements between school districts if a student committed a sex crime in one district and transferred to another school.

Other states have already addressed the issue. Iowa state law mandates sheriff’s offices let schools know when they have a student who is registered as a sex offender, and schools may distribute the names of students who are on the registry to parents, as those names are already public information.

Matt Carver, who is the Legal Services Director for the School Administrators of Iowa, said the law helps keep all students safer. It ensures both building administration and district-level personnel know when students who are required to be on the sex offender registry enter schools.

“We would say that it’s important and it is something that we’re pleased to have in Iowa…as another means of ensuring that school administrators are aware of the presence of these sex offenders within the district,” he said. “They can ensure that other students are protected and so that they can ensure that the student [the offender] is protected as well.”

Carver said once local law enforcement tells building administration about offenders, the administration is required to tell the school board. Then, the board will hold a closed session and work with the student and their family to determine their educational accommodations.

“It’s just a means of ensuring there’s an awareness of the presence of students so that all students can be protected,” he said.

As well as serving in the state senate, Hensley was a special education teacher at the Capital City School in Topeka. Capital City is known for taking in students who have been through the juvenile court system and often have been expelled from other schools. As a result, students’ criminal histories were well-known among teachers and administrators.

He said people who work with students should know the students’ backgrounds.

“It’s a matter of transparency to know that students have that kind of background,” Hensley said.

Hensley said students could be given an individual education plan (IEP), which could mandate their class participation is different from other students. For instance, students with sex offenses could report to a separate room for some classes to isolate them from the general school population.

“You could put them on a special plan for their school day,” he said.

THE CASE FOR AND AGAINST CHANGE

Senior Nicole Berkley found out about Gleghorn’s criminal record after she had been in the same Humanities class with him for a semester, and said she would feel safer in classes if teachers knew those things about their students.

“I feel like the teacher definitely should know, and if he [the teacher] feels like one of the students looks uncomfortable because they’re around that person, they should be able to maybe get them moved out of the class if people are getting uncomfortable,” she said.

Some people feel differently. Matthew Herbert, who is a government teacher and serves on the Lawrence City Commission, said juvenile criminal records often lead to lost opportunities and re- incarceration of offenders. He said once that information is known, the educational environment for students who have committed crimes may be compromised.

“As it relates to young students, our goal is to enable them to be productive and successful and keep them out of that vicious cycle,” Herbert said. “Information is important, but it also leads to judgment, stigma and ultimately a different treatment in the classroom. Though I do not speak for other teachers, administration or law enforcement, I personally do not have an interest in knowing a student’s criminal background. What they have done in the past will not affect the way I teach them senior government or freshman civics.”

Further complicating the issue is the background of the offenders. Teens who commit sex crimes are often people who have been subject to similar abuses in the past, said Hays, of the Sexual Trauma and Abuse Center.

“A lot of the research shows that people under 18 who commit sex crimes have also been victims of sex crimes,” she said. “That complicates the situation a lot, and makes it a lot harder to know when that person should be punished and in what way and what kind of treatment they might also need.”

Church of the Kansas Association of School Boards said the challenge is balancing the rights of offenders, victims and other students.

“The bottom line for the school is that they have an obligation to educate all students,” Church said.

**Editors Note: This story was updated April 25. The Budget staff appreciates feedback on stories. All comments challenging the accuracy of the story have been checked. The story has been updated to reflect new information. Specifically, news of James Gleghorn’s record had come to the attention of at least one administrator before his February arrest, although the administrator wasn’t notified by law enforcement or courts. There remains no requirement that schools are notified when students are convicted of sexual offenses.