Funding ‘blocked’ from public schools

District copes with $2 million in budget cuts, class sizes rise as result

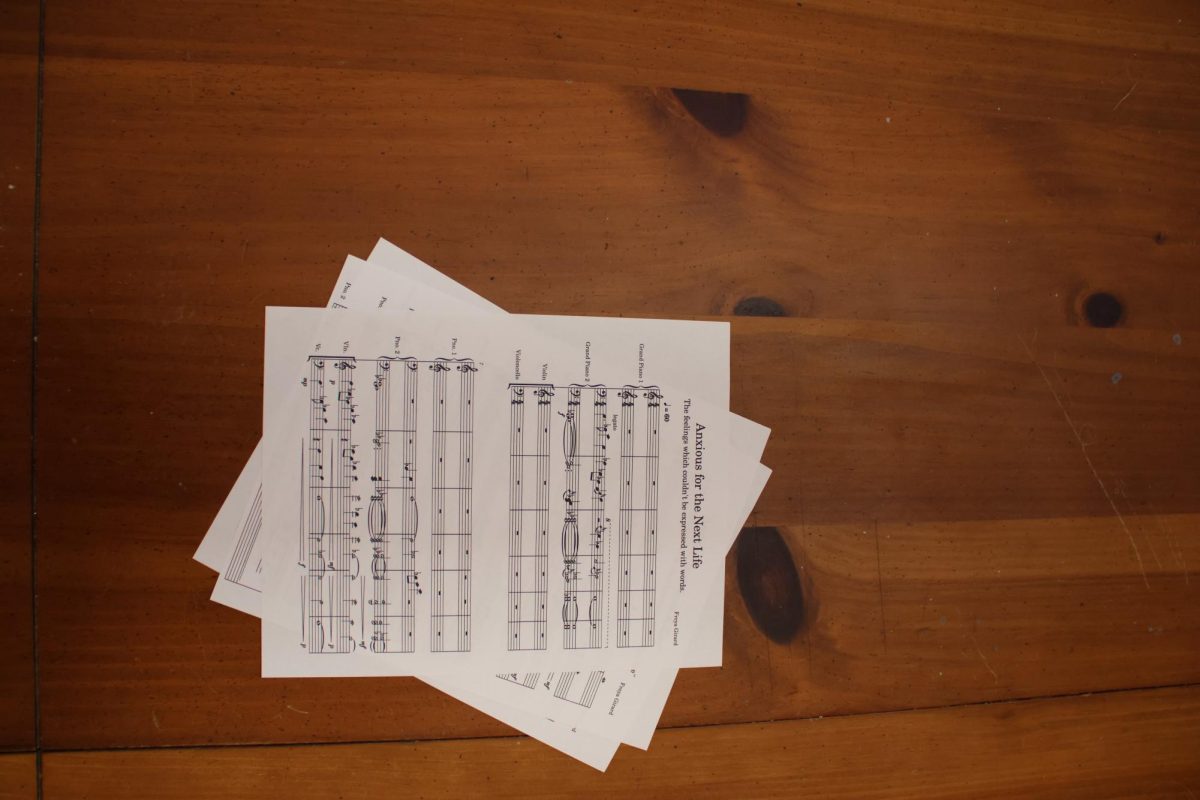

Biology teacher Ann Foster teaches a class of 24 students in 2015.

September 29, 2015

While students were on summer break, USD 497 scrambled to patch together a school budget that would shield students from a $2 million funding deficit the district faced after state lawmakers last spring changed the way they fund schools.

The cuts were made primarily at the administrative level, leaving most programs and resources intact. But with stagnant funding coming against a growing student population, staffing levels at LHS are strained.

“Most of that will be handled at the district office,” principal Matt Brungardt said of the budget cuts. “I think the thing you can see is really an increase in class sizes.”

The staffing ratio has grown from 20 students to one teacher to 21.25 to one this school year. As a result, the school let go of four staff members last semester before the cuts were announced. Because some classes are smaller individual teacher may have classes far larger than usual.

“Our class sizes were really pretty good when you look at all of the schools around us, so they bumped our ratio a bit to save a little bit of money,” Brungardt said.

He said teachers last year taught 90 to 100 students, but that has increased to 100 to 115 this year.

“We are full,” debate coach and English teacher Jeff Plinsky said. “It’s not untenable, but we’re fuller than it has been in the past. The end result of that is going to be that teachers have less time to spend individually with students.”

Less one-on-one interaction is only one problem teachers must cope with. Having additional students means more time spent grading, especially for teachers who have writing-heavy courses.

“If every essay takes 10 minutes to grade and you’ve got 30 extra students that’s 300 extra minutes of grading,” Plinsky said. “That’s an extra five hours of grading every time you assign something.”

The higher-than-average student population is likely to continue growing through the beginning of the year. This year’s student population is up to 1,577 from last year’s 1,456. In addition, Brungardt said transfer students can account for 50 or 60 more students throughout the first semester.

Although this is usual, schools will have a more difficult time absorbing the extra students.

In past years, if enrollment increased, the district would have received more money from the state. However, the new funding system of block grants is no longer directly tied to enrollment.

The block funding plan was championed by Gov. Sam Brownback as his administration faced with a massive fiscal deficit brought by tax cuts.

Brownback claimed the previous school funding formula was over-complicated and inefficient and pushed his plan as a simpler alternative.

His plan eliminated the existing funding formula and ultimately cut $127.4 million from public education. It will stand though the 2016-2017 school year while a new formula is written.

“The reality is the old formula isn’t bad, it just needs to have the funding in it to support what it was designed to do,” district finance director Kathy Johnson said. “Anytime you don’t fund it appropriately, it’s going to have flaws.”

By the time the formula was eliminated in May, base state aid per pupil was near the amount that it had been when the system was created in the 1990s, Johnson said. While the system called for per pupil funding of nearly $4,800, it was actually providing $3,852 per student, she said.

Johnson said while the district has had expected difficulties coping with the losses, the cuts were not surprising.

“The writing on the wall for this state having difficulties has been there for a number of years,” she said. “It’s not that it’s been a new thing, it just kind of keeps getting pushed off… At some point you are going to have to face the music unless you have a new revenue source, and if that never happens… you’ve got to figure out how to make it work another way.”

As a response to signs of funding difficulties from the state, USD 497 has been putting money into its reserves in anticipation of future funding shortfalls from the state.

The district has also been getting by on funds from several other sources.

The 2013 bond issue that funded construction of the College and Career Center and construction at area schools is being used to purchase new furniture for classrooms. Those purchases would have usually come out of the district’s general operating fund or capital outlay fund, so Johnson said that the bond issue has offset the costs of the upgrades the district has made.

USD 497 also has a larger-than average virtual school program that provides additional funding from the state.

The district is also receiving a block of startup money for the new classrooms in schools and at the CCC.

“We’re in a little bit of a unique situation from a lot of districts,” Johnson said.

While Lawrence has been able to find ways to bridge the gaps that block funding has created, some districts have more variable to worry about.

Cities with large populations of high-need students, such as those that do not speak English, are no longer getting the additional funds to assist with the extra resources they require.

That means cities like Wichita, where there are a lot of people who have been relocated from natural disaster areas, are unable to hire additional staff to translate and assist those students.

While the district used its reserves to minimize the effects of funding reductions this year, those reserves cannot serve as a long-term solution.

“If you have a savings account and something happens…you dip into your savings account,” Brungardt said. “The district has cash reserves, and they’re dipping into the account. The question is, how long can you keep dipping into your savings account?”

The funding situation beyond the 2016-2017 school year is unknown, Johnson said.

Even if state lawmakers write a new formula, there is no guarantee it will be adequately funded.

“As educators, all we can really do is come into the classroom and teach the days that we are here and hope that the people making those decisions make good decisions,” Plinsky said. “It’s not a real hopeful attitude, but it’s where we’re at right now.”