Uncovering Lion Legacies

Reporting pushes for diversity and equality in the LHS Hall of Honor

May 11, 2022

Letter From the Editors: Telling Lost Stories

By Cuyler Dunn, Tessa Collar and Arien Roman Rojas, Editors-in-Chief

Lawrence High School is filled with rich, diverse history. This year our coverage has sought to encapsulate that diversity. We covered sections of our school’s new mural that highlight civil rights protests held at LHS. We analyzed how racial slurs are used in schools and how they harm minority students.

This coverage led us to dig deeper – where has our coverage, and our school, not fully encapsulated the diverse history of our student body? What better place to look than at our school’s Hall of Honor?

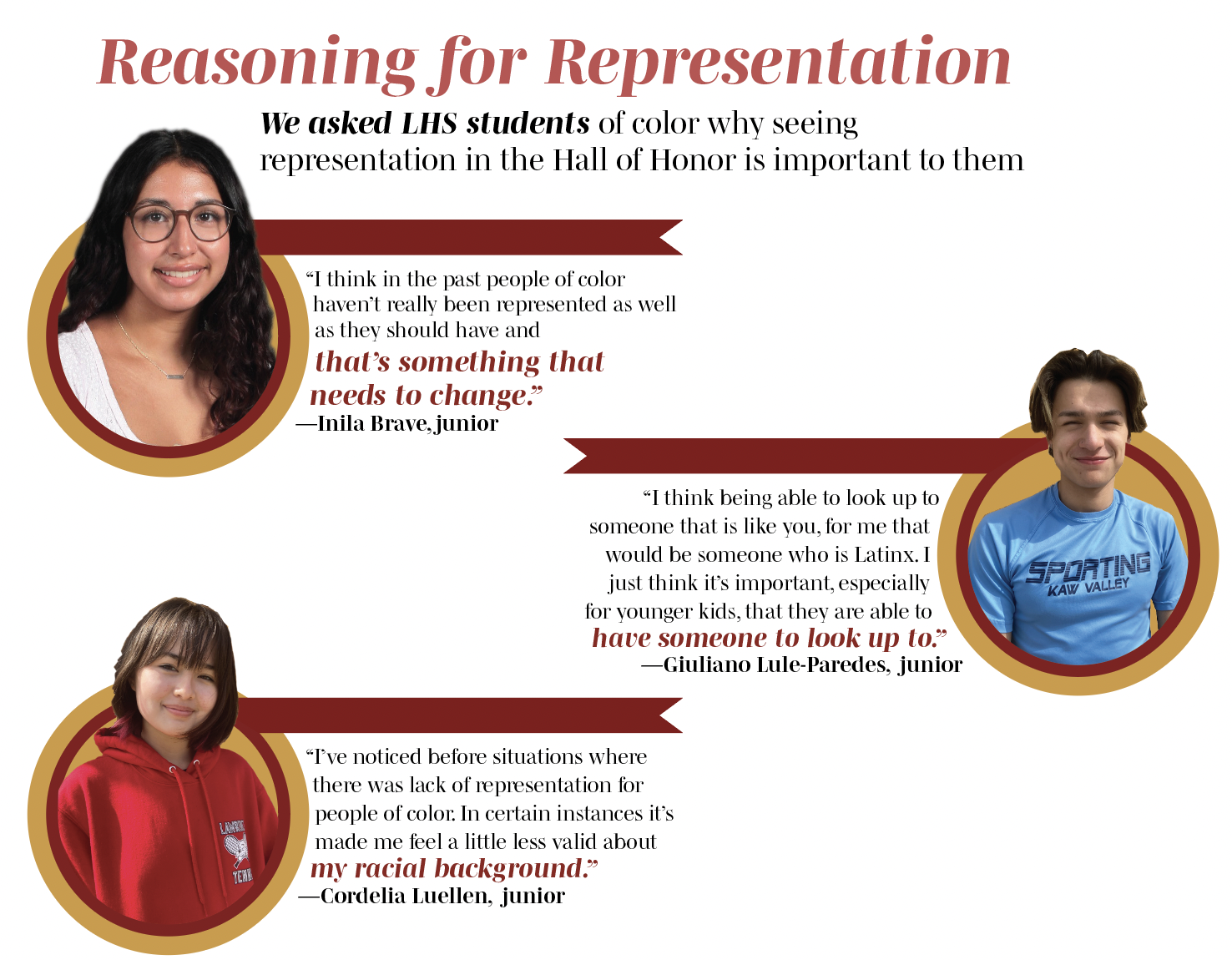

It came to our attention that our Hall of Honor is not an accurate representation of the history of our student body, specifically students of color.

The goal of this project is to tell the stories that are missing from the Hall of Honor. We hope to raise awareness of this lack of representation. The Hall of Honor should be a form of inspiration to students, but we feel there is a disconnect between the demographics of our student body and the people that are included in the Hall of Honor.

Fulfilling our goal requires a few reporting tasks. In this project, you will find multiple people of color who were instrumental and impactful in the development of LHS and the city of Lawrence who we believe deserve recognition in the Hall of Honor.

We also feature current people of color in the Hall of Honor. These people have made a significant influence on their city, state and world since graduating from LHS.

Finally, we talked to our student body, the driving force behind this project, and talked with them about why this kind of representation matters.

We hope that our reporting accurately reflects the strength, diversity and history of LHS and inspires change that creates more diverse and reflective spaces in LHS institutions in the future.

Leonard Monroe was the youngest of eight children and the son of a carpenter. Born and raised in Lawrence, Monroe became a distinguished athlete in track and basketball during his time at Lawrence High School (then Liberty Memorial High School).

Monroe experienced discrimination throughout his entire life, an obstacle that got in the way of his education and athletic desires. Back in the 1940s, Liberty Memorial had integrated some of its sports, like football and track, but others like basketball still had separate teams for black and white students.

“They didn’t integrate the basketball team until 1950,” Monroe said in an interview with Alice Fowler. “As a matter of fact, I was one of the first ones to be on the Lawrence Lions, the first black to be on the Lawrence Lions.”

Monroe was the second-fastest quarter-miler in Kansas, obtaining him offers from universities during his senior year of high school. But Monroe only had one college in mind: the University of Kansas. Unfortunately for Monroe, the track coach at KU, Bill Eason, refused to let Monroe run on account of his race.

Despite disappointing encounters like the one with Eason, Monroe didn’t let the discrimination he experienced derail his life. He was a man with a great deal of adversity. Since he couldn’t run track at KU like he wanted, he decided to join the Air Force.

During his time in the Air Force Monroe tried to sign up for classes at LSU but was once again stopped on account of his race. His only option was finding 19 other African Americans who were willing to commute to another school, not the LSU campus, in order to study.

Given the additional challenge, he decided to stay in the Air Force. Eventually, he was discharged to study at a nine-month electrical school in Kansas City since he had experience as a front-line electrician in the Air Force. During his job search he discovered that the job market was riddled with racism and he would be unable to find a job.

He joined an aerial demonstration team called the Thunderbirds and was eventually recruited by the Walker Air Force Base in Roswell, New Mexico in 1958.

Monroe met his wife, Jaqueline, in Roswell. After getting married he was stationed in Vietnam, had a son, and returned. He left for Germany where he had two daughters and worked in the Aerospace and Ground Equipment field at the Rhine Mainz Air Force Base.

During his time in the military, Monroe became quite accomplished. He received an accommodation medal for his time in Vietnam and was afforded titles for his exemplary leadership. Although only a tech sergeant, Monroe was promoted to Brass Chief of the squadron, where he took over the branch.

Monroe was in for a major surprise when, during a conversation with the major of the squadron, he was made Master Sergeant. “Boy, that was the biggest surprise,” he said, “because you have to have two years in grade to make Master Sergeant and I only had eighteen months at the time.”

He ran that branch for three years, later served in Taiwan, and was assigned to McConnell Air Force Base located in Wichita after that. Monroe was made Senior Master Sergeant at that branch, and often returned to visit his family in Lawrence.

After serving for 23 years in the Air Force, Monroe decided to look forward to a different occupation. He got a job with City Hall as the superintendent of a city garage. He received a flag to commemorate his work for the city after he retired.

“I was just swept off my feet really,” he said. “I mean, the whole thing was for me.”

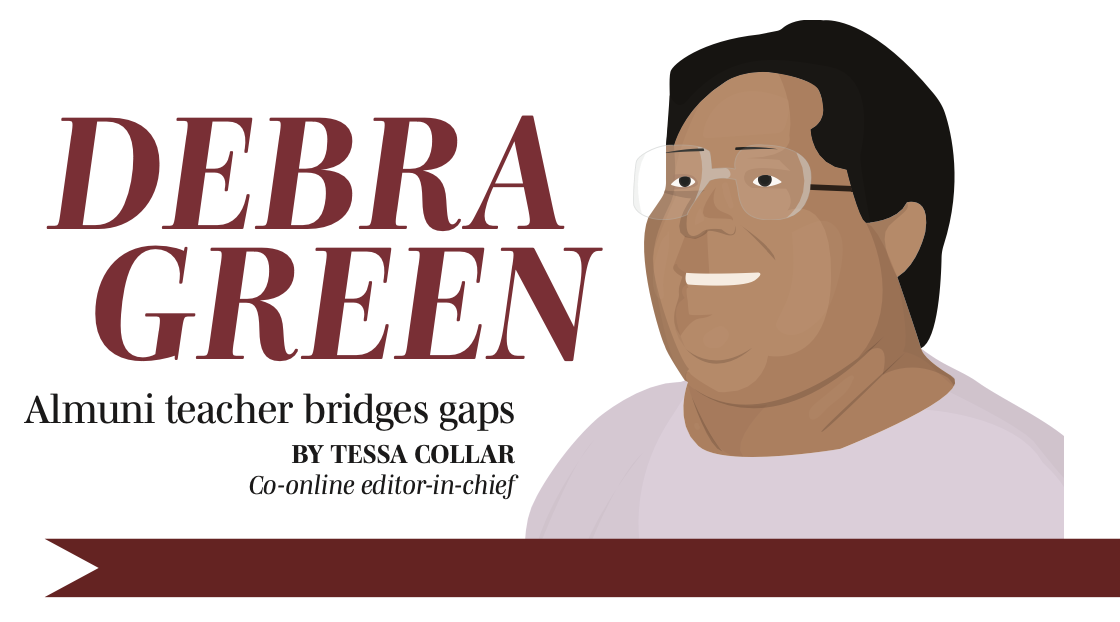

A math teacher of 31 years, Debra Green was born May 18, 1951 in Lawrence, KS and graduated from Lawrence High School in 1969.

Green taught math at LHS for over three decades, positively impacting the students she taught and going beyond her required duties for students. Being of Native American and African American heritage, Green defied the odds and broke down barriers.

Green’s family has deep roots in Lawrence, with her great-grandparents settling in the area in the 1860s as sharecroppers, after being freed from slavery during the Civil War.

Following Green’s passing in 2012, the Lawrence Journal-World published an article titled “Family and friends remember LHS math teacher Debra Green,” commemorating her contributions to Lawrence High and the wider community.

Green expressed her appreciation for Lawrence High in getting her on the path she wanted to pursue.

“I liked Lawrence High at the time I came through because… I got the best teachers, it allowed me to get eight hours of calculus for college credit before I got out,” Green said in an interview with Curtis Nether in 1977 as part of the “Lawrence/Douglas County African American Oral History Interviews.” “Really, those teachers that I had gave me a sense of direction on where I wanted to go.”

Green also influenced younger family members, such as her great-nephew, Jelani Ragins.

“She is part of my inspiration for wanting to go into the education field,” said Ragins, a 2021 Lawrence High graduate. “The things she accomplished as a Black woman during her time are phenomenal.”

Jack Hood, Lawrence High social studies teacher, taught with Green at Lawrence High for several years. Hood emphasized the significance of Green’s life and her impact on the community.

“Her life could be a book,” Hood said. “She and her family have been so important to the history of Lawrence, and I think Kansas University athletics back in the day. She influenced so many people as a teacher and a community leader. She bridged gaps between the different communities of Lawrence.”

Oldham recalled the caliber of Green’s teaching and her way of connecting with students.

“Debra Green was a professional teacher in the highest regard,” Oldham said in a Lawrence Journal-World article. “She had high standards, but if you had a problem she always had time to talk. Debra touched lives in a positive nature.”

Although he didn’t experience Green as a teacher, Ragins only heard positive comments of her dedication and care in her classroom.

“Many people who went to LHS and had [Green] for a class always will share her love for the students,” Ragins said. “Anyone that I talk to always mentions how much she cared and poured into seeing her pupils succeed.”

A vital part of the Lawrence civil rights struggle of the 1960s and 1970s, John Spearman Sr. was born on June 28th, 1928 in Lawrence, KS.

John Spearman was an integral part of his community, helping to make Lawrence the place it is today. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Spearman was a member of the Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy (LLPD), the Lawrence chapter of the NAACP, the Concerned Black Parents, the Lawrence Human Relations Commission and the first African American USD 497 School Board member.

“He always believed that Lawrence was a place worth improving, even if he had to fight to do it,” John Spearman Jr, Spearman Sr.’s eldest son, said in a Lawrence Journal-World article “Rights leader helped shape city,” run after Spearman Sr.’s death honoring his contributions.

Spearman played on the all-Black basketball team, the Promoters, while at Liberty Memorial High School. During World War II, Spearman served in the U.S. Army in Japan. Beginning in 1961, Spearman worked at a local Hallmark plant as a cutter, and ended his career in 1994 as an industrial engineer.

“Listening to America”, written by Bill Moyers, former White House press secretary, details conversations Moyers had with Spearman Sr. while visiting Lawrence to write his book.

In “Listening to America”, Spearman Sr. described what it was like to live as a Black person in Lawrence during his lifetime.

“When I grew up in Lawrence the Blacks were pretty invisible people,” Spearman Sr. said. “There are men on the school board who don’t realize I went to school with them. They just weren’t aware of me. You seldom saw blacks mentioned in the newspaper, certainly not on the society page.

Everything in this town was segregated except the schools. While I was in high school you could only participate in noncontact sports if you were black. Track — not basketball or football. The year after I graduated, a black was nominated by the students to run for class president–the first time— but the principal stepped in and eliminated him. Housing was segregated, the drugstores were segregated, the restaurants were segregated, jobs were segregated.”

Spearman Sr. emphasized his commitment to ensuring his children had a better high school experience than himself and that they knew their self-worth.

“I made up my mind that my children wouldn’t spend their high school years how I spent mine,” Spearman Sr. said in “Listening to America.” “I started very early making sure they knew they were as good as anybody living, anybody walking on the earth. If they suffered oppressions or injustices, I told them, it had nothing to do with their own self-worth. It has to do with the white man’s ignorance and pride. I told them to strive for what you want, what you know is right. But don’t deal from feelings of inferiority, frustration and bitterness. That isn’t what I wanted for them.”

Michael Spearman, Spearman Sr.’s son, noted the impact his father had on Lawrence and the changes that came from his work.

“He worked with so many individuals and organizations to make Lawrence a better place,” Michael Spearman said. “My father impacted so many people and helped bring about so much necessary change.”

Michael Spearman reflected on his parents’ involvement in this effort for the integrated pool in Lawrence in the 1960s.

“My parents were members of the organizations that waged this battle against a very resistant community,” Michael Spearman said. “I remember going with Mom and Dad to demonstrations against the segregated pool, the Jayhawk Plunge, as a very young child.”

“Taking the Plunge: Race, Rights, and the Politics of Desegregation in Lawrence, Kansas, 1960,” an article written by Rusty Monhollen, focuses on activism in Lawrence during the 1960s, and specifically on the efforts to create an integrated public swimming pool.

Monhollon included Spearman Sr. and his wife, Vernell, in his discussion of the LLPD and the fight for desegregation in Lawrence.

“Members of the LLPD shared a commitment to social justice,” Monhollon wrote. “John Spearman Sr. and Vernell Spearman, African Americans who were lifelong Lawrence residents and the children of social activists, were typical LLPD members, working quietly and diligently for racial equality.”

State Representative Barbara Ballard echoed the sentiment that Spearman played an important role in the advancement of Lawrence’s civil rights.

“I don’t think he just sat back and said someone else could do it,” Ballard said in “Rights leader helped shape city.” “He participated in making Lawrence what it is today.”

Michael Spearman noted the vast differences between the place Lawrence is today as opposed to the segregated place it was in the mid-1900s.

“I think it says something that most people living in Lawrence now wouldn’t recognize the Lawrence that my father lived in,” Michael Spearman said. “In fact I doubt that most would find it hard to believe the Lawrence in which my father grew up ever existed. But it did.”

Spearman passed away July 4, 2007.

Michael Spearman emphasized his parents’ lifelong involvement in making Lawrence the place it is today, referring to the battle to establish the integrated swimming pool.

“I suspect that most people living in Lawrence today will find it hard to believe that the white citizens of Lawrence were so strongly opposed to what seems so uncontroversial today,” Michael Spearman said. “But it was a battle my father and mother helped to wage and eventually win. That it is now an almost forgotten memory had a lot to do with my father, my mother and those who fought along with him to make right so much that was so wrong.”

Inspiring the Future

Current Hall of Honor inductees speak on the importance of diversity

Dr. Larry Kwak

Dr. Larry Kwak is a world-renowned physician and scientist who has pioneered breakthrough innovations in immunology and cancer vaccines. His accomplishments led him to be named one of TIME magazine’s “100 most influential people” in 2010. He was also awarded the 2016 Ho-Am Prize in medicine. The Ho-Am Prizes recognize people of Korean heritage who have made significant medical advances. Dr. Kwak credits a lot of his growth to a high school mentor who sparked his interest in the field. We reached out to Dr. Kwak to discuss the Hall of Honor and the lessons he learned during his time at LHS.

Here is our conversation about the Hall of Honor slightly edited for clarity:

Dunn: Describe what you think your accomplishments mean to your community?

Dr. Kwak: I am privileged that my calling to help people is also my chosen occupation. In high school during a summer internship at a hospital lab, I did menial tasks, but at the end of each day, my mentor invited me into his office to look at slides of cancer cells. He challenged me to ask the question of why there were there and the even bigger questions of whether they could be harnessed to fight cancer someday.

That question inspired me to pursue a career as a physician and scientist and my lifelong quest to harness the immune system to fight cancer. Inventing new treatments for cancer that can be offered to patients who don’t have other options is what still gets me excited about going to work every morning. Making an impact on cancer earned me recognition in the time 100 and the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in South Korea.

Dunn: What advice would you give to current Lawrence High Students?

Dr. Kwak: As you think about your future, think big, in terms of maximum impact. We all have a universal calling to help others and improve humankind. Developing excellence in your chosen craft will require sacrifice and perseverance.

Dunn: What is your vision for Lawrence High’s Hall of Honor?

Dr. Kwak: The purpose of awards and honors is to inspire those around us and the next generation.

Doug Coffin

Doug Coffin has been a professional painter, sculptor and mixed media artist for more than forty years. A Potawatomi and Creek Indian, Coffin grew up on Haskell Indian Nations University’s grounds and graduated from Lawrence High School in 1964. Coffin has used Native American inspirations in his art to create his unique artistic style. He’s a recognized artist that has had his art displayed all around the world and a wonderful example of how connecting with your roots can help you pursue your passions and succeed in life. Coffin was inducted into LHS’s hall of honor in 2006. We reached out to him to ask about the importance of representation in the Hall of Honor and what it meant to him to be inducted.

Here is our conversation about the Hall of Honor slightly edited for clarity:

Roman Rojas: What’s the most important thing you learned during your time at LHS?

Coffin: There are a lot of different groups that form throughout the process of going through high school. There are the sporty people, artsy people, in those days you notice those obvious differences. But at the same time, the class of 1964 Lawrence only had one high school so everybody was thrown into the same kind of environment so you felt that you were up against the same things and you were going to get along with everybody as much as you could. As far as that people did seem to get along as far as I could tell.

Roman Rojas: What impact do you think diverse representation could have on students?

Coffin: People need to respect the differences and realize that people are the same. We’re all related. There are all kinds of success stories and they all started off at Lawrence High. It shows that people can achieve their own successes no matter where they are. People have done some remarkable things. Part of the common bond is going to the city of Lawrence. People of color worked as hard as anybody.

Roman Rojas: What did it mean to you to be inducted into the Hall of Honor?

Coffin: Well I got the call that I was inducted and I started laughing which I don’t think they expected. I was like “Did you get the wrong number? Why are you calling me?” I wasn’t the best student, the brightest student, the hardest working student but again I had my vision of the singular thing of what I wanted to do.