Drug prevention funds lost

Funds not pursued, could be difficult to regain

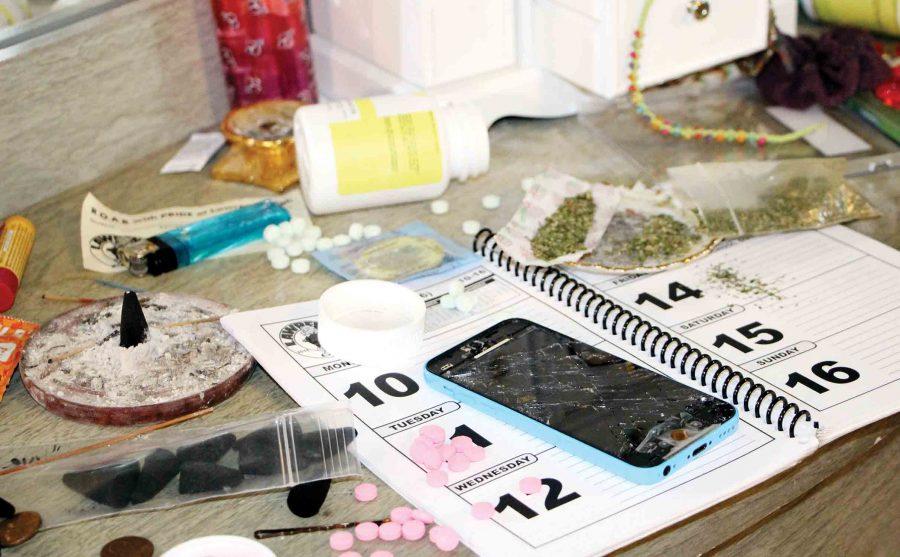

Problems – For years, LHS benefited from the work of a prevention specialist who helped address the school’s high rate of drug use.

October 20, 2016

Students at Lawrence High use drugs more than average Kansas students yet the district decided against continuing to pursue grants that helped bolster prevention efforts.

Prevention work continues in other ways but lacks the support of a prevention specialist with time dedicated solely to preventing drug use as well as bullying and other issues. And the ability to revive those efforts in the future would only be harder because schools no longer collect the data they need to make the case they have a problem.

“At the district, we felt we could do it in-house,” executive director of student services Kevin Harrell said. “So that’s when we spoke with buildings about what are the specific programs and activities that are useful and that need to be done. And the building looked at that and decided to make sure that those things happened at the building with existing staff.”

Existing staff, however, does not include former prevention specialists like Diane Ash, who worked with students in FYI, taking panels of high school students to elementary and middle schools.

Her career in the district and the grant money funding the district’s prevention program ended simultaneously, after USD 497 declined to allow a coalition of community members to pursue leftover City Alcohol Tax funding. It was funding the district had used to pay for the program Ash led at LHS and another at Free State. The district wouldn’t have had to write the request, as the coalition offered to do that work, people involved in the effort said.

Throughout the program’s history, the grants were written and administered by the Douglas County Citizens Committee on Alcoholism (DCCCA), a non-profit organization often pronounced “decca,” which has expanded its services to bordering states and now works with many issues beyond alcoholism. Jen Jordan-Spence, a former DCCCA employee and current grant-writer for the city of Gardner, Kan., was taking care of the paperwork and just needed the go-ahead from the school district to bring it to the city.

“I was writing the grant,” Jordan-Spence said. “I was the one writing it. They would then though be financially responsible, which is what DCCCA did for five years.”

The school district and DCCCA had long been able to make the case that the extra efforts were needed. In 2014, 43 percent of 12th-grade students in Douglas County reported using marijuana at least once — seven percentage points more than the state average. The county also surpassed the state average of students who had used psychedelics at least once by two percentage points.

Such data, which was compiled as part of the annual Communities That Care (CTC) survey, helped justify prevention efforts. But that data is longer being compiled — a change that could endanger future prevention efforts.

In 2014, the Legislature passed a bill that inhibits the ability of schools to survey students on substance abuse and other risky behaviors. Under the new law, schools must now get parental permission before students can be surveyed about morality, family life and risk behaviors. Participation in the CTC plummeted in many areas of the state, and Lawrence High no longer participates.

But by opting out of the survey, the district will now face difficulty in getting grants in the future. Those grants require quantified evidence of need and without the survey data, LHS won’t have proof of the need.

“Especially if there are grants that are being applied for, usually a grant will require reports that use some sort of a measure and the Kansas Communities That Care is a recognized instrument for measuring change,” CTC survey coordinator Nancy White said.

According to data from the CTC survey, from 2000 to 2014 — while the survey was still being administered in USD 497 — the percentage of Douglas County 10th and 12th grade students who had used marijuana at least once was consistently higher than state averages for each year. Data like this allowed the DCCCA to prove to organizations with grant money that Douglas County did, in fact, have higher instances of marijuana and psychedelic drug use, proving a need for funding for prevention. The survey also showed where efforts had been successful, including a drop in binge drinking during recent years.

Over 25 years, Ash said as many as 18 prevention specialists were funded at one time through grants, including one from the federal Drug-Free Communities Act and one from the City Alcohol Tax via the Lawrence Social Service funding advisory board.

“The district has not ever funded money for prevention,” Ash said. “Different people in the district, starting 25 years ago, thought it would be a wonderful idea to have a position completely focused on developing prevention programs around alcohol prevention, around bullying, around a lot of different issues that concern young people.”

The prevention program, which had money for counseling for students with addiction or at risk of addiction, has an uncertain future. FYI has continued to carry on a few of Ash’s programs, but students have fewer opportunities to talk to peers and younger students as they did when Ash worked at LHS. Because she didn’t have a teaching schedule, she was available to spend the bulk of a school day off LHS campus or wherever needed.

Assistant principal Mark Preut has stepped in, along with English teacher Kelsey Buek, to continue some of Ash’s programs, such as the Bullies to Buddies and Cultural Diversity programs. Buek is the club sponsor.

“My role is facilitating Ms. Buek’s, what she’s doing with kids, then contacting Tracy Urish as the secretary to contact the elementary schools to start arranging times,” Preut said. “The mental health team, actually, goes out to the various presentations. We feel like it’s important to have somebody that has that training because issues come up through the course of a conversation and having somebody with that mental health training background there to facilitate and help out.”

Although many have stepped in, Ash played an incredibly active role that is difficult to truly fill.

“Obviously, filling Diane Ash’s shoes, it’s huge,” Preut said. “And she did so much stuff, above and beyond, that was part of FYI, that I don’t know that we’ll find somebody to fill those shoes. But, we have lots of people who have stepped in to help provide those prevention services.”